Links and Resources

This is an edited version of the website that the citizens’ assembly used during the process. All the videos that contain identifiable information has been removed, in accordance to the requirements of the UAHPEC.Questions about options

Recycled water for drinking

Q: Has the quality of recycled water been proven over many generations (long-term analysis)?

A: Direct Potable Reuse has been in operation in Windhoek, Namibia for more than half a century (since 1968).

A: Since the 1980s, thousands of water reuse projects have been developed around the world, and it is estimated that more than 200 water-recycling schemes are in operation in the European Union.

A: Many states in the USA use direct recycled water

Q: Some people may not accept the purified recycled water from sewage, but can accept that from stormwater. Can these two resources of wastewater be treated separately?

A: Stormwater and wastewater are different and are already treated separately – they have different pipe systems underground. It’s important to understand that stormwater might look cleaner than wastewater but is actually quite dirty. Water from roofs is more likely to be safer and cleaner than water that has run over the roads.

Q: I've read that there are higher nitrogen and phosphorus levels in purified recycled water? Is this true? Isn’t it also the case that some minerals have to be added to Advanced Treated water, because those plants remove all things non H2O?

A: Advanced water treatment (including desalination) remove all minerals from water, so some that are important to receive via the water supply need to be added back at the end.

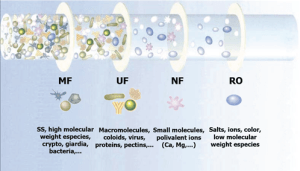

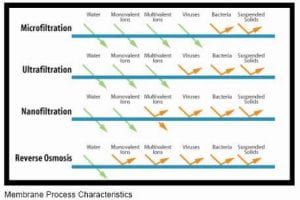

Q: A far as I understand, conventional prion detecting methods don't work very well in water so would we have to hope that nanofilters in waste-treatment are able to efficiently remove prions?

A: Prions can be removed by effective filtration and reverse osmosis. Treating wastewater or seawater to a drinkable standard would require both filtration and reverse osmosis in the advanced water treatment plant.

UF Purification versus Microfiltration, Which Process To Choose For Your Application?

https://www.safewater.org/fact-sheets-1/2017/1/23/ultrafiltrationnanoandro

Q: If direct recycling is cost effective then why efforts are not made to create more awareness among people to accept this method?

A: The issue seems to be a political one rather than a scientific one. The Water Services Association of Australia has produced this document about the growing acceptance of recycled water options which might be useful:

https://www.wsaa.asn.au/publication/all-options-table-lessons-journeys-others

Q: Does the water taste any different - can one identify which water is recycled or which is not?

A: You cannot tell the difference because the water from all water treatment plants is ‘pH balanced’ to make it safe and taste good.

Q: Will indirect and direct treatment plants be turned off when the storage is full?

A: This can be done but it is better to plan for the amount of water needed rather than turning systems on and off. The recycled water systems can continue to be used when dams are full, rather than drawing from them, leaving that water storage for times when demand is higher or there is a drought.

Q: Which method needs to be run less and can save cost?

A: Direct treatment for drinking is cheaper to run, because although they make the same water, it takes money to pump around the recycled water into water courses/dams etc.

Differences between the recycled water options

Q: What are the key differences between options 3, 4, and 5?

A: Direct (option 3) = wastewater goes into an advanced water treatment plant and is then pumped into supply

A: Indirect (option 5) = wastewater goes into an advanced wastewater treatment plant then into a lake, river or groundwater storage, then into advanced water treatment, and is then put into supply

A: Water in option 4 is not for drinking. It would be conveyed in different pipes and must be kept separate from drinking water networks.

A: Drinking water must meet very strict guidelines before it is put into supply. These guidelines ensure that the water is safe to drink.

Q: Can we get option 3 in enough scale for both options – drinking and not drinking? Then we wouldn’t need option 4.

A: Yes – option three at 150 MLD would be enough for drinking and non-drinking. Also note that there are strict quality standards that need to be met whether for drinking or other use (ie. you have to treat wastewater well before you put it into the environment anyway)

Q: If option 5 is more expensive, why is it more common? Is it just a cultural thing or are there other reasons for not using option 3? Why is the carbon cost to build this option so much higher than option three?

A: There are some storage (resilience) benefits of indirect recycling (option 5). With this option, a reservoir (storage) would need to be built.

A: Option 3 doesn’t require a reservoir to be built. With the Rosedale option previously identified, the treated water would need to be pumped uphill to the built storage lake so there is an additional energy requirement to operate that option.

Recycled water vs Desalination

Q: How would a desalination system compare to waste treatment? (cost, efficiency, purity)

A: Cost: wastewater treatment costs less than desalination

A: Efficiency: waste treatment is a lot more efficient, with higher water volume recovery. Reverse Osmosis is required for both but there is less pressure on the treatment plant for wastewater treatment, because you have to process so much more water with desalination to get the same amount in the end (yield)

A: Purity: Risks are a bit higher with waste treatment because seawater has lower concentration of contaminants.

Q: What about evaporation systems in waste treatment?

A: Evaporation systems can be used to reduce the water portion of water-based wastes by converting the water portion to water vapour. This does not contribute to water supply but could reduce the volume of treated water being released to harbours/waterways.

A: Evaporation technologies are sometimes used to treat the waste stream from desalination, thereby recovering salts and other minerals, and reducing/eliminating the discharge of brine, but these processes are currently very expensive. Evaporation ponds are most efficient in the arid or semi-arid areas (that means, not Auckland!).

Desalination technology

Q: Is this the only option for desalination? Is there anything that is more efficient/sustainable?

A: The methods presented represent what is currently possible/practical. The limits of what we might do by 2040 are not known. Nothing is set in stone and nothing has been decided.

A: This is a constant area of research internationally as desalination becomes more widespread as a source of water. If chosen as a way forward, significant investment would be made on how to do this well – protecting people and the environment and improving efficiency.

Q: Has anyone approached the Navy for information as they have experience of desalination on ships. Could we run a pilot programme?

A: We have asked the Navy – this may be classified information. We are making enquiries and will come back to you.

Location of facilities, and where the water goes

Q: Where would the treatment plants go, and who gets the water? Has the site already been decided or is this still up for discussion? (for all potential sources)

A: Nothing has been decided yet – the option would have an impact on the site, and this is what the assembly is for

Q: Are poorer communities or certain areas going to receive more direct purified water than others if we don't mix it in a reservoir? Will there be a mix of water sources to those areas?

A: Recycled:

If the recycled water source is in the North, there may not be enough volume to shift it south. The shore will still end up with a blend. In Summer it will have more water coming in from the south to blend, while in winter it would provide the majority of the shore water.

For Mangere it will depend on how it’s configured.

A: Desalination:

No particular site has been specified yet. It could be either in the Hauraki Gulf (easier to manage) or out on the West Coast (better for mixing but harder to manage)

If Hauraki it would likely be Rosedale (where our wastewater assets are)

Q: Option 4: How much of this would be used for residential vs. commercial use?

A: Non-potable use would be for organisations and businesses who have need for lower quality water. It is not practical to construct the pipe network necessary to provide non-potable water for general residential use.

Rain tanks

Q: How would we go about implementing rain water tanks if this option were chosen?

A: Even if it were mandated the cost and responsibility of installing rain tanks would be borne by the household. If this were subsidised, the cost of subsidisation would be paid for by the billpayer. The water utility would still need to have capacity to supply the household during dry spells unless the mandated tank size was 2×25,000 litres. Therefore, we still would need another source until everyone had two large rain tanks or are prepared to go without water during a drought. This is why this option is so expensive.

Q: Yield – rain tanks: Does the 10-15% saving from water tanks represent the current number of tanks? Or does it relate to if everyone had a tank?

A: It is 15 million litres. This is the possibility for 1/3 of Auckland roof space having tanks attached.

Q: Why didn’t we make it compulsory to have rain tanks plumbed to toilets?

A: Building regulations are set at the national level. Watercare encourages customers to have rain tanks but we know that plumbing them into the house is expensive.

Q: Rain tanks: does it matter how old the house is?

A: Age of house is not critical but it is easier to plan for and install tanks during building. Retrofitting to older homes can be expensive.

A: A few things would be required to make this work:

– Space for tanks

– Metro supply during droughts

– Backflow prevention

Q: Why can’t rain tanks be plumbed into the toilets?

A: They can be. This is done in some new developments. However, when the rain tank is empty, toilet flushing water must come from the metropolitan supply. It’s also more expensive than the larger source options (per household) and the cost will be borne by the household, not the water provider.

Q: In the early 60s, there were water tanks, the water in them we used for drinking, washing, cooking. We had no pumps for the tanks. Why is it different now?

A: It isn’t different, it’s about how reliable they are in summer and how densely packed our city is. In summer you need space for 2x 25,000 litre tanks to be self-sufficient.

About Koi Tū

Koi Tū: The Centre for Informed Futures is an independent, transdisciplinary think tank and research centre at the University of Auckland.

We generate knowledge and analysis to address critical long-term national and global issues challenging our future.

Address

Koi Tū: The Centre for Informed Futures

The University of Auckland

Level 7, Building 804, 18 Waterloo Quadrant, Auckland Central 1010

Newsletter: Subscribe here

Twitter: @InformedFutures

Contact

Future transport email:

ccl-transport@auckland.ac.nz

Future water email:

ccl-study@auckland.ac.nz

Phone: 027 271 9907